Medieval Baltic

The Viking Age

- A sewing basket

- Skjoldehamn hood and tunic

- Garðar and Heynes mittens

- Mitten article translation

- Triangular shawl

- Whipcord braiding

- Images of Norsewomen

- Belt Hardware in Norse Female Graves

- Open-Fronted Apron-Dress (PDF)

- Apron, strap, and underdress textiles (PDF)

- Runic embroidery and leatherwork

- Moksha puloker braids

- Omega brooches (PDF)

Runic Embroidery and Leatherwork.

When people think runes, they may think of Vikings and runestones. Maybe some of the graffiti left by Varangians in the Hagia Sophia (Knirk, 1999) or the Piraeus Lion (Pritsak, 1981). Others may think of runes as tools of divination, and having magical properties. But very few people think of the futhark as being just another alphabet for scribbling messages.

The medieval wharf district of Bryggen, in the town of Berggen, Norway, was the amazing find place for an extensive corpus, in both Latin and Old Norse, that illustrates the use of medieval runes in daily life. Tags to attach to goods to denote ownership (Spurkland and van der Hoek, 2005;184), messages from home (Haavaldsen and Ore, 1997f), and love notes (Haavaldsen and Ore, 1997g), are just some of the inscriptions found.

But item B605 is different, because it is a shoe vamp 'bearing decorative embroidery in runes' (Spurkland and van der Hoek, 2005;183). B605 was deposited before an 1198 CE fire (ibid.), circa 1180-1190 CE (Rundata, 1993; N B605 M) and like many of the Bryggen writings was in Latin. The fragment is 353 mm long and 160 mm wide (Haavaldsen and Ore, 1997a).

B605 was embroidered with ...am(or)u-iciþomnia..., which has been normalised to amor vincit omnia (love conquers all) (Haavaldsen and Ore, 1997b). It has been suggested that the other shoe may have read et nos cedamus amori (let us give in to love), completing the poetic sentiment of Virgil's Eclogues (Spurkland and van der Hoek, 2005;184).

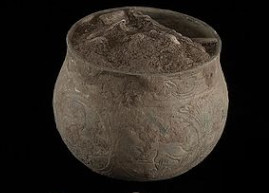

Left: Embroidered 12th century shoe, B605. After Roesdahl and Wilson [ed.] (1992; 360-1).

Right:Photograph by Hannah Young, from the Unimus Portalen site. Accession no. BRM0/052927.001 Used here under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license.

A second 12th century shoe upper, B663, was also embroidered (Rundata, N B663 M), with the futhark (Haavaldsen and Ore, 1997a, 1997c), while another contemporary shoe piece is incised with as yet untranslated runes (Haavaldsen and Ore, 1997d; Rundata, 1993; N B8 M).

Incised 12th century shoe, B008. After Haavaldsen, A. and Ore, E.S. (1997d).

According to Swann (2001; 61), there are a total of 5 shoes from Bergen embroidered with runes. The embroidery was worked by first inscising the leather, and linen or silk thread was used for tunnel stitching (Swann 2001, 59-60). Satin stitch, cross stitch or satin stitches were used (ibid.).

These examples illustrate that in 12th century Bryggen, at least, decorating leather with runic marks and embroidery -- in both Latin and Old Norse-- was done. However it would be stretching the truth to say that this shows that runic embroidery can be applied to any other textile. As of writing, I do not know of any other examples of rune-embroidered or otherwise decorated items of clothing.

The second issue, is of concern to modern-day people who believe in an inherent magical power of runic characters. In this context, the embroidery of amor vincit omina is interpreted as a love charm or wish (Macleod and Mees, 2006; 65). Yet, we cannot know for sure the mindset of your average, amorous medieval Norwegian, and it is just as likely that this probable pair of shoes were simply decorated with a poetic verse and presented to their object of affection (ibid., 54-5). Although Macleod and Mees consider writing out the futhark to reinforce the power of magical charms (ibid., 42), it is not the use of a runic script that imparts magic, but the words that were written down.

It may also simply be a way of a gentleman to impress a girl with his runic literacy, or it may form part of a traditional, European betrothal gift, with its origins dating back to at least the 6th century (Starkey, 2004; Swann, 2001;61). In any case, while there is some evidence for seemingly non-magical runic decoration on clothing, it is up to the individual making those clothes to decide if some exotic-looking lettering is a good idea.

2022 Update

As of September 2022 only B605, of the six runic-decorated shoes from Bergen, are photographed on the Unmus Portalen database. In case that changes in the future, the Universitetsmuseet i Bergen lists their accession numbers on the portal site as:

- Runic inscription B008: BRM0/004450.001.

- Runic inscription B453: BRM0/042375.001.

- Runic inscription B605: BRM0/052927.001.

- Runic inscription B606: BRM0/078137.001.

- Runic inscription B654: BRM0/021542.001.

- Runic inscription B663: BRM0/077726.001.

Bibliography

- All links checked 23 September 2022.

- Haavaldsen, A. and Ore, E.S. 1997. Runes in Bergen (Bergen: Norwegian Computing Centre for the Humanities)

- Haavaldsen, A. and Ore, E.S. 1997a. Inscriptions on artefacts other than wooden sticks

- Haavaldsen, A. and Ore, E.S. 1997b. B605

- Haavaldsen, A. and Ore, E.S. 1997c. B663

- Haavaldsen, A. and Ore, E.S. 1997d. B008

- Haavaldsen, A. and Ore, E.S. 1997e. B606

- Haavaldsen, A. and Ore, E.S. 1997f. B149

- Haavaldsen, A. and Ore, E.S. 1997g. B017

- Knirk, J.E. 1999. Runer i Hagia Sofia i Istanbul Nytt om runer 14; 26-27.

- Macleod, M. and Mees, B. 2006. Runic Amulets and Magic Objects (Boydell Press)

- Nasjonalbiblioteket [National Library of Norway] Runic inscriptions from Bryggen in Bergen

- Pritsak, O. 1981. The Origin of the Rus’ [vol. 1] (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press)

- Roesdahl, E. and Wilson, D.M. 1992. From Viking to Crusader: The Scandinavian and Europe 800-1200 (New York: Rizzoli International Publications, Inc.)

- Rundata. 1993. Samnordisk Runtextdatabus (Uppsala: Department of Scandinavian Languages, Uppsala Univeristy.)

- Spurkland, T. and van der Hoek, B. 2005. Norwegian Runes and Runic Inscriptions (Boydell Press)

- Starkey, K. 2004. 'Tristan Slippers: An Image of Adultery on a Symbol of Marriage' in E. Jane Burns [Ed.] Medieval Fabrications: Dress, Textiles, Cloth Work and Other Cultural Imaginings (New York: Palgrave Macmillan); 35-54.

- Swann, J. 2001. History of Footwear in Norway, Sweden and Finland (Stockholm: Kungl. Vitterhets Historie och Antikvitets Akademien)