Medieval Baltic

The Viking Age

- A sewing basket

- Skjoldehamn hood and tunic

- Garðar and Heynes mittens

- Mitten article translation

- Triangular shawl

- Whipcord braiding

- Images of Norsewomen

- Belt Hardware in Norse Female Graves

- Open-Fronted Apron-Dress (PDF)

- Apron, strap, and underdress textiles (PDF)

- Runic embroidery and leatherwork

- Moksha puloker braids

- Omega brooches (PDF)

Versions of this article appeared as:

Ulfvíðardóttir, Á. 2010. "Belts of Viking Women" Tournaments Illuminated 175; 9-12.

and as

Ulfvíðardóttir, Á. 2013. "Belts in Viking Women's Graves." Quid Novi 35(3): 2-10

If you are looking for a specific version, please refer to one of the above editions.

The Tournaments Illuminated article, due to length constraints, did not include the entire bibliography. It is online here.

There is also an appendix of belt buckle finds. It is online here.

Belts in Viking Women's Graves.

Belts are an everyday accessory we might not often think about. They keep our pants up, cinch clothes in attractively at the waist, are a handy place to hang gloves and pouches from, and within the SCA can have the additional function of showing status and rank for certain people (such as the convention of a white belt signifying the wearer is a knight). But the evidence of belts being worn by Viking-age Scandinavian women is rather slim – only a handful of female graves and cremations contain belt hardware, fewer still have detailed excavation reports that show a buckle was found at the waist. But, in conjunction with indirect evidence, saga references, and what women of other contemporary cultures wore, it is still possible to gain a general, albeit limited, picture of what a Norse woman’s belt may have looked like.

The Evidence for Buckles and Strap-Ends.

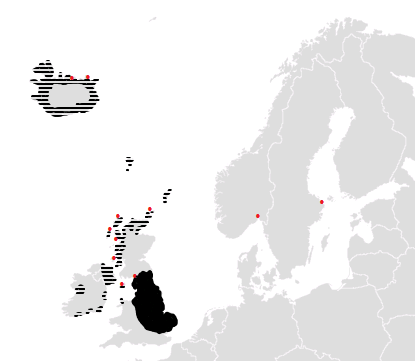

The easiest sort of belt to document is one with metal fittings and hardware – they are less likely to break down in the soil after burial (Larsson, 2008), and treasure hunters are more likely to find, and report, a metal artifact over textile remains (e.g. Portable Antiquities Scheme, 2007, 2010). Not all buckles found in female graves were included, however, as in many cases it appears they were associated with horse tack (Pétursdóttir, 2007) or jewellery (Bratt, 2001a,b), and are therefore not indicative of a belt. The vast majority of finds occur outside of the Scandinavian peninsula, in areas of Norse settlement.

Caption: Map showing areas of Norse settlement in the 9th and 10th centuries. Solid black areas are Danish settlements, while stripes indicate Norwegian colonies. Dots represent location of belt hardware finds, after Montgomery et al. (2003) and Wikimedia (2006).

This small collection of female graves with belt fittings, can be divided in to three categories of evidence:

- Graves containing paired tortoise brooches, and belt hardware at the waist.

- Graves without paired brooches, but with belt hardware at the waist.

- Graves containing paired tortoise brooches, and belt hardware within the grave, or found nearby.

While the first category of evidence would, naturally, be the best sort, its rarity forces us to consider all of the available evidence.

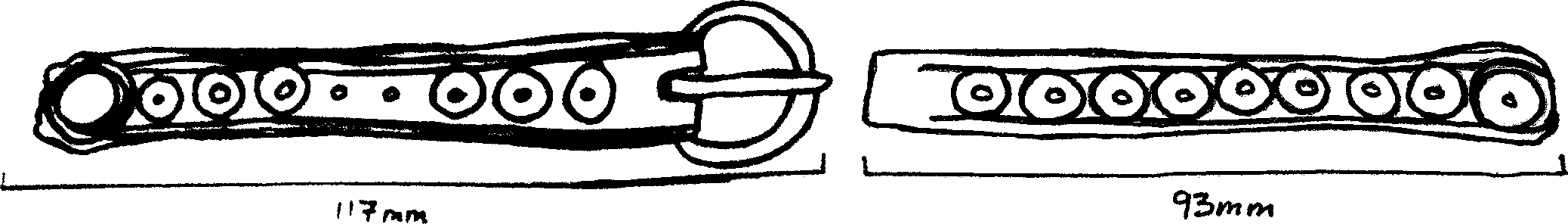

Cnip headland on the Isle of Lewis is unique in this corpus, as it is the only interment with a detailed archaeological report describing the position of objects within the grave, as well as tortoise brooches. A 10th century female skeleton, was discovered with tortoise brooches, and a bronze buckle and strap end set, both found resting on her lower ribs (Welander et al., 1987; Gordon, 1990). It appears that leather fragments remained between the bronze sheet-metal plates, indicating that she was buried wearing a short belt (Welander et al., 1987). Interestingly, a strap-end in the same style, also with leather remains, has also been discovered in Kroppur, Eyjafjarðarsýsla, Iceland although that burial was without oval brooches (Hayeur-Smith, 2003ab). It is likely that both women from Cnip and Kroppur were of a mixed Norwegian/British Isles background (Hayeur-Smith, 2003b), or had another strong connection to the islands. An analysis of the tooth enamel of the Cnip woman showed that she was native to the British Isles, although she may have been of Norwegian descent, and it is probable her oval brooches were heirlooms (Montgomery et al., 2003).

Above and below: Buckle and strap-end from Cnip, and strap-end from Kroppur. Click to enlarge.

Two further graves have been reported as revealing a buckle at the waist, although neither woman appears to also have been buried wearing tortoise brooches. Grave sk 27 at Cumwhitton, Cumbria, England is that of a woman wearing a copper-alloy buckle that had traces of sealskin between the plates (Watson, 2009-10; Oxford Archaeology North, 2009). St Patrick's Isle, a tiny island between Scotland and Ireland was the site of a grave containing a probable woman. A buckle was found at the waist, while the strap-end hung down to the knee. 'Near to, but below' the buckle were some fragments that may have been contained by, or were part of, a pouch or purse suspended from the belt (Freke and Allison, 2002).

There are graves, either disturbed, excavated in a haphazard manner, or loose finds near previous burials, where both tortoise brooches and belt hardware have been discovered, although it is difficult to say for certain what the belt may originally have been associated with. For example, in 1963, a farmer was digging a hole in order to bury a cow at Westness, on the island of Rousay, and unearthed the remains of a 9th century woman and her newborn child. Placing his cow on top of the skeleton, he disturbed the grave contents so the original placement of objects, including two Anglo-Saxon style strap ends, is unknown (Henshall, 1963; Graham-Campbell and Batey, 1998; Batey, 2005). A contemporary grave in Kaupang, Norway, contained a bronze belt buckle, a pair of tortoise brooches and an equal-armed brooch (Blindheim, 1976). A female grave from Daðastaðir, Iceland, contained a copper-alloy belt buckle ‘said to be adorned with two highly stylized animal heads’ and a pair of tortoise brooches (Hayeur-Smith, 2003a). Where precisely this buckle was found in the grave is unknown.

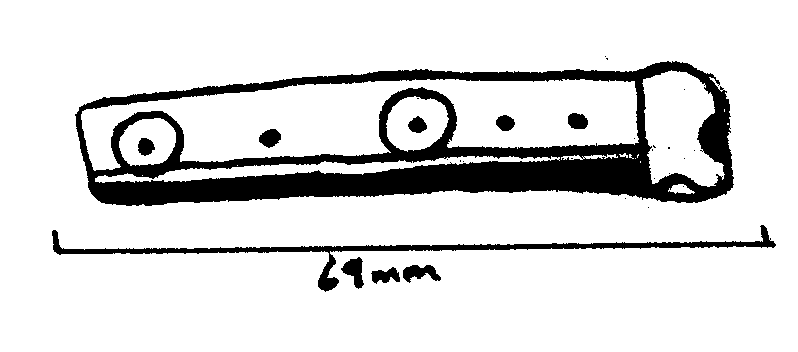

A silver-plated bronze buckle, decorated with a niello inlay of knot work, was found along with a possible belt mount and paired tortoise brooches at Bhaltos, Isle of Lewis (Gordon, 1990; Grieg, 1940; Macleod, 1915), believed to date from the 9-10th centuries (National Museums of Scotland; 000-100-102-641-C). However the sizes of the belt mount and buckle are noticeably different, with the mount almost twice as wide as the buckle. On Reay, Caithness, a small tin-plated bronze buckle was found in a 10th century grave with a pair of tortoise brooches (Gordon, 1990; Curle, 1915). All of these finds provide evidence that buckles were present in female graves, but they cannot be used to categorically state that these Viking Age women wore a belt at their waist.

Left: Buckle and belt-mount from Bhaltos, Uig, Isle of Lewis (Macleod, 1915). Not to scale.

Right: Buckle from Reay, Caithness (Curle, 1914).

Finds that can only be tentatively associated with a female grave include a buckle loop from Cruach Mor, on the Isle of Islay, Scotland, which was discovered as a loose find in the 1970s; however previously in 1958 a Norse burial was discovered at the same site (Gordon, 1990). There is also said to be a female grave from the Inner Hebrides at Kildonan, Eigg, containing a buckle; however the references given point towards a male burial, as a sword was also found (Gordon, 1990; Grieg, 1940).

Of the nine examples of belt hardware I have been able to find, that mention their dimensions, the majority (4) are approximately 15 mm wide. Two items were 25 mm wide, and the remaining three were 35 mm wide. Of the three finds that mention the presence of belt remains, all of them are leather (Welander et al., 1987; Hayeur-Smith, 2003a; Watson, 2009-10). Due to such a small sample size, it is impossible to draw any firm conclusions, but it appears that there is some evidence for Norse, or Celtic-Norse women wearing leather belts with metal decoration. It also seems quite likely that these were also slightly narrower than belts worn by men – men’s belts in one survey averaged at about 20 mm wide (Jomsborg, 2006).

Exceptions and Parallels

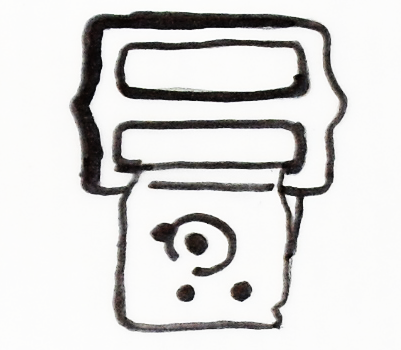

There are female graves that contain characteristically Norse items as well as buckles and strap ends outside of these typically Norwegian areas. It has been reported that strap-ends, and a single belt buckle, have been found within female cremation graves in Swedish Birka (Jansson, 1986; Mälarstedt, 1986), although Geijer reconstructed female Norse dress without any belt (Geijer, 1938). This is because these strap ends are believed to have been part of a 9th century fashion trend –they modified and worn as jewellery (Ericsson and Carlsson, 2001). Birka cremation grave Bj 456, identified as female but containing no paired brooches, included a buckle (Mälarstedt, 1986; Historiska Museet, 2010), although there is no way of knowing how or why it was originally worn.

Above: Belt buckle from female cremation grave Bj 456. Photograph by Ny Björn Gustafsson, SHMM, used under a Creative Commons 'Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 2.5 Sweden' License.

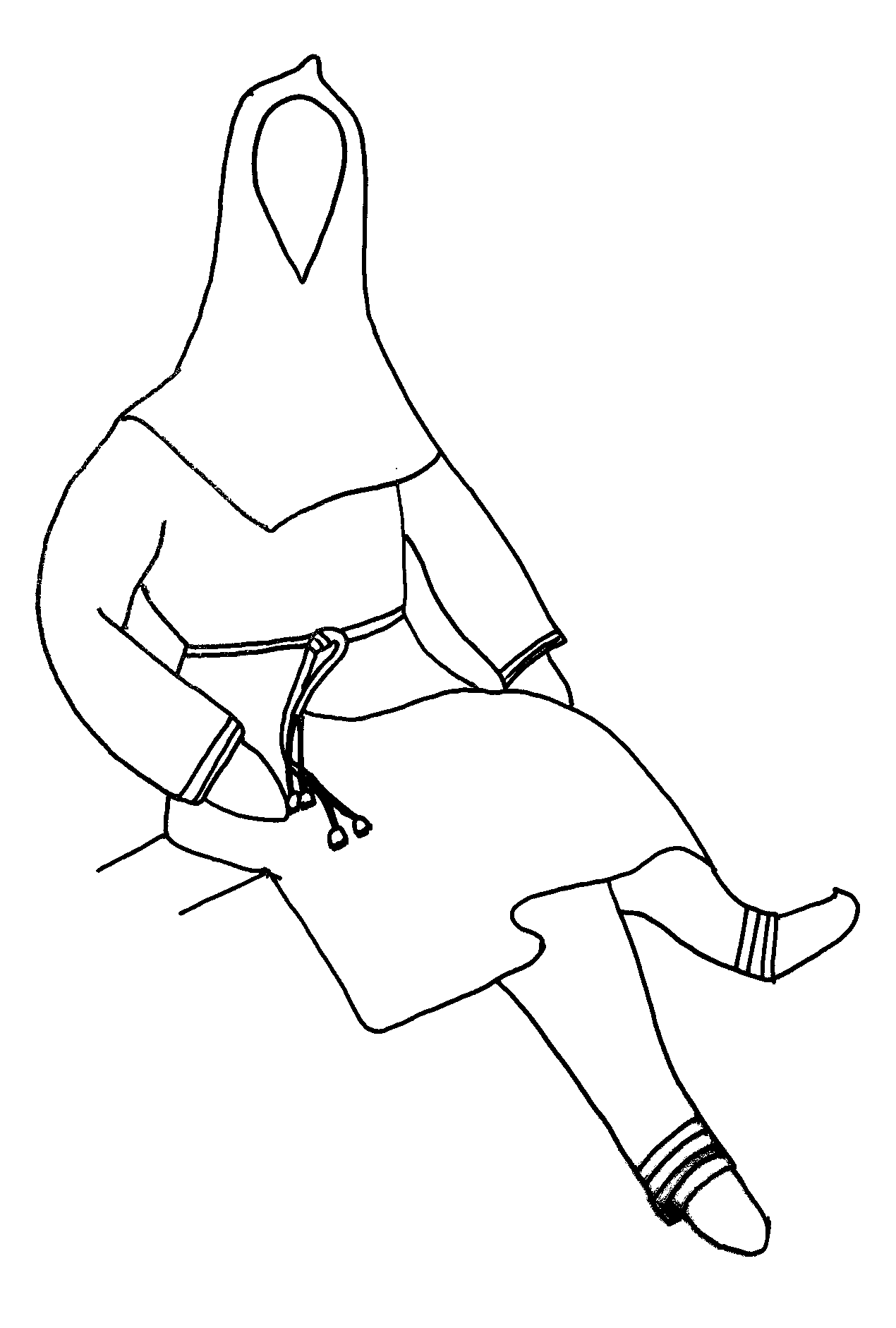

A carved figure on the cart buried on the 9th century Oseberg ship could also be interpreted as a woman in a short gown, wearing a tasseled belt at her waist (Universitetsmuseenes Fotoportal, 2010). Interestingly, the appearance of this woman strongly resembles the dress of the 10-11th century Skjoldehamn bog find. Located in Arctic Norway, and believed to be a Saami woman (Løvlid, 2009a,b), she was wearing a woolen, plaited belt (Gjessing, 1938) that has been recently reconstructed as ending in small, decorative tassels (Løvlid, 2009a).

Left: Drawing of a woman decorating a panel of the Oseberg cart. Redrawn from Universitetsmuseenes Fotoportal (2010).

Right: Drawing of the Skjoldehamn outfit. Redrawn from Narmo (2009) and Vesterålen Info (2009).

Further east, on the other side of the Norse homelands, a double cremation burial from Timerevo, outside of Yaroslavl, Russia, appears to have bone and metalwork remains of each body placed at either end of the grave. The teenaged girl was buried with a strap end, strap mount and circular brooch of bronze, but no paired brooches (Duczko, 2004; 195). Duczko describes this as a Norse grave, presumably dated from the late 9th to the mid 10th centuries, (ibid. 191-3). However due to the nature of cremations, it is impossible to say for certain if this belt hardware was worn at her waist. A 10-11th century chamber grave of 'Scandinavian type' from Kiev, contained a 16 to 18 year old woman and a bronze belt buckle (Ivakin, 2004-5), once again without paired brooches. In a reconstruction drawing, this buckle has been interpreted as fastening a belt that a leather purse was suspended from (ibid.) This grave also illustrates the importance of knowing the position, and any modification, of belt fittings within the grave. Her necklace included two Magyar-styled silver belt fittings, that had riveted suspension loops.

Along with the Birka buckle, Rus strap ends, and the carving from Oseberg, there is further indirect evidence that points towards some sort of belt being worn by Norse women. The woolen fragment from Hedeby Harbor, that has been interpreted as a panel in an apron dress, has a long strip where the fabric was worn down and fulled, approximately 15 cm parallel from the top edge (Hägg, 1984). This has been presumed to have been from the dress rubbing against something that has been interpreted as a belt (Hägg, 1984). This is often assumed to be a tablet woven sash by re-enactors and re-constructors (Priest-Dorman, 1999; Persdotter, 2001, Krupp, 2004); however the panel had presumably passed through the hands of numerous owners before it was used as caulking rags on a ship; there is no way to know what style of belt was worn.

It seems to be generally assumed, because of the paucity of evidence for leather belts, that fabric belts may have been worn by women. Neighboring non-Norse cultures may also provide glimpses of what form these fabric belts may have taken. In the eastern Baltic, tablet woven belts are known, including a 15 mm wide example from grave 56 at Luistari, Finland, but there are no examples of female graves containing belt fittings (Lehtosalo-Hilander, 1984). Viking-Age Livs, from a territory that encompassed parts of modern-day Latvia and Estonia, are believed to have worn belts made from woolen sprang (Zarina, 1985; Zeiere, 2005; Latvijas Nacionālais Vēstures muzejs). We also have some idea of how woven garters for men may have been constructed. 10 mm wide wool bands from the Mammen burial, often described as garter bands, have been reconstructed using finger weaving, pointing towards another possible textile technique (Hald, 1980; Kaland, 1992).

Belt Pouches

The next question is why did these women wear a belt? It may have been merely for fashion, or to visually communicate the ethnicity (Hayeur Smith, 2003b) or status (Price, 2004) of an individual, in life as well as in death. We know that Finnish women, for example, used their belts to hold their mittens and apron in place (Lehtosalo-Hilander, 1984). Today, we treat belts as a handy place to hang a pouch, as our Viking-Age clothes do not come with pockets. In our pouches, we would store ID cards, money, keys, maybe a mobile phone, medication-- the list goes on. But 1000 years ago, Norse women seemed to only rarely carry pouches, and if they were attached to a belt in a burial it was because the woman was likely a seiðr practitioner (Price, 2004).

Seiðr, sometimes translated as sorcery (Price, 2008), was practiced by a section of Norse pre-Christian society, often female, who carried with them staffs, 'amulets and charms of various kinds, including preserved body-parts of animals, and... mind-altering drugs such as cannabis and henbane (ibid.). These items had to be carried somehow, and it appears that the typical solution was a belt pouch (Price, 2004). For example, a 10th century grave from Fyrkat, Denmark, is believed to be that of a völva, or seeress. It appears that she was wearing a belt, and a pouch, because at her waist was a group of henbane seeds, 'which suggests that they had originally been gathered in some kind of belt-pouch made of organic matter that has since decayed' (ibid.). Eiríks saga rauða, thought to have been written down in the 13th century, also mentions a prophetess called Thorbjorg who was described as '...hon hafði um sik hnióskulinda, ok var á skióðupungr mikill; varðveitti hon þar í taufr...' (She wore a belt, soft like punk, and there (on it) was a large pouch of skin; where she kept her magical charms safe.) (Gordon and Taylor, 1956, own translation). This strong connection between the wearing of a belt pouch and sorcery may be an issue for those with Norse personae, who may not wish to inadvertently advertise their skills in pre-Christian religious practice. Another reason pouches may not have been worn is the apparent fashion for chatelaine-style hanging of personal belongings from tortoise brooches or a tool brooch (e.g. Hägg, 1996; Pettersson, 1968).

Conclusions

Too often, differences in material culture between different Viking-age Scandinavian groups have been overlooked in favor of a more generic interpretation. One such example may be the wearing of belts, which appears to have varied in fashion according to place and occupation. Western Norse settlements, such as the Hebrides and Iceland, appear to have had a fashion for wearing narrow leather belts with a buckle and/or strap end. There is also evidence of strap ends and buckles from cremation graves in Birka and the lands of the Rus, which may point towards leather belts being worn there, too. By and large, however, the evidence is indirect and it seems much more likely that if a belt was worn, then it was made of textile and was not preserved. It seems items hanging from such a belt are rare, possibly because there was a fashion for chatelaine-style hanging of personal belongings from the tortoise brooches or tool brooch (e.g. Hägg, 1996; Pettersson, 1968), or because of cultural associations with seiðr, which may be overlooked by costumers.

Although other re-enactors have extrapolated from these few finds that belts with associated buckles and strap ends indicate a universal Viking-world fashion (eg. Jomsborg, 2006), it is unlikely that this is the case. While today we are inclined to see the Scandinavians of the period as being generically Norse and fairly homogeneous, it is unlikely that this is how they saw themselves. Fashions in clothing varied in time and place, such as between Swedish Birka (Geijer, 1938), Gutnish Gotland (Kaland, 1992), Danish Hedeby (Hägg, 1984) and Norse Dublin (Heckett, 2003), so why not fashions in belts and sashes, too? The vast majority of the belt-fittings discovered are believed to have originated in Celtic-Norse regions (Blindheim, 1976), and I am firmly of the opinion that a belt, probably leather, with a buckle and/or strap end was a fashion worn by only a particular sub-set of women; those with connected to Norway and the western Norwegian colonies. Archaeology is unable to reveal to us how these women viewed themselves, and their cultural identity, and what statement they intended to make in death by wearing Norse tortoise brooches, and Celtic belt fittings (Hayeur-Smith, 2003b).

Turn this Celtic-Norwegian fashion to your advantage, to paraphrase Mistress Thora Sharptooth: ‘Hang a date and a locale on your persona, and be able to demonstrate it in your choice of clothing’ and impress everyone with your not-so-generic Viking-Age outfit (Priest-Dorman, 1996)!

Bibliography

Please see the complete bibliography.

©2012, Rebecca Lucas. Text, photographs, and diagrams not covered by other licenses: