Medieval Baltic

The Viking Age

- A sewing basket

- Skjoldehamn hood and tunic

- Garðar and Heynes mittens

- Mitten article translation

- Triangular shawl

- Whipcord braiding

- Images of Norsewomen

- Belt Hardware in Norse Female Graves

- Open-Fronted Apron-Dress (PDF)

- Apron, strap, and underdress textiles (PDF)

- Runic embroidery and leatherwork

- Moksha puloker braids

- Omega brooches (PDF)

A Viking-Age Ladies' Sewing Basket.

When sitting at displays or events, to keep my hands busy I will try to spin wool, or sew clothes. But it began to feel wrong that I was sewing with thread on a plastic spool, so I tried looking for alternatives but could only find information about the renaissance (de Holacombe and de Neuville, 2006) or later periods, where there was more artwork and written sources to refer to. Faced with the task of putting this information together, it is styled in the same manner as the Filum Aureum's Period Workbox article, however with different sources and conclusions.

Baskets and Boxes

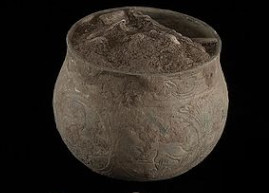

Surprisingly, there is a wide range of boxes, including basket-woven ones that date from the Viking Age. Legged chests, often called 'sea chests' include two from the early 9th century Oseberg burial (Roesdahl and Wilson, 1992; 269-70), 10th century Cumwhitton, Cumbria (Watson, 2009-10; 16) and the Mastermyr chest from 11th century Gotland (Arwidsson and Berg, 1983). Bentwood boxes, made by wrapping a thin piece of wood around a base include the late 9th century Gokstad 'backpack' (Schuster, 2009), 16-22 Coppergate, York (York Archaeological Trust, 2009 search term 'box') and a box from Heddeby (Hall, 1984; 91). Finally, there are remains of at least three coil baskets, one from Lund, Sweden, one from the Oseberg find, Norway (SCA Basketry, 2009; Universitetsmuseenes Fotoportal, 2010), and a 30x60mm undated example from the Farm Beneath the Sand, Greenland (Østergård, 2004; 42-3).

However, there are two containers that we know for certain were being used to house sewing tools, a bucket-like wooden box found on the Oseberg ship (Lewins, 2003 and Brøgger, 1921; 6) containing balls of thread and wax, and seeds of flax and woad, (Brøgger, 1921; 6), and a small chest of maple from Cumwhitton containing 'various tools for textile working,' possibly including some needles (Watson, 2009-10; 14, 16).

Due to the lower costs of buying a coiled basket over a wooden chest or bentwood box, I use a basket with coiled lid.

My coiled basket. Originally from Ikea, where it is called Fryken.

For a photo of the Oseberg basket, please see Engevik jr. (2002: 54).

Scissors, Snips, Shears, Awls and Knives

Scissors, shears and snips are all found in the Viking-Age archaeological record. The difference between snips and shears is mostly size -- snips are good for cutting thread or light fabric, but shears would be used for heavier textiles. Scissors, almost identical in shape to modern, plain kitchen or sewing scissors have also been found.

Scissors

Photos by Yliali Asp (left) of SHM 19732, and Sara Kusmin (centre and right) of SHM 11570.

Shears

Photos by Yliali Asp of SHM 5208 (left), Matthias Toplak of SHM 22293 (centre and right).

Snips

Snips (here, an arbitrary classification of shears 15cm long or smaller):

Photos by Yliali Asp of SHM 5208 (left), Elisabet Pettersson of SHM 12360 (centre) and Sara Kusmin of SHM 11570 (right).

Images of scissors, shears, and snips sed under a Creative Commons license.

For a photograph of shears from the Oseberg burial, search for 'saks Oseberg' at the Universitetsmuseenes Fotoportal site.

Needles and Cases

Although bone needles are more commonly seen in some re-enacting circles, possibly because they look more unusual and therefore more historical when sewing, both bone and metal needles were used during the Viking Age. Just like today, different sizes and types of needles are better suited to certain tasks over others, so a chunky bone needle may be excellent for naalbinding, but poor for sewing.

Bone Sewing Needles

Photos of SHM 5208 by Yliali Asp.

Metal Sewing Needles

Photos of SHM 3421, SHM 34000, and SHM 32458 by Yliali Asp.

Images of sewing needles used under a Creative Commons license.

Needlecases

Bone and antler needles can be fragile when particularly small and fine, and whatever the needles' material you would want to keep them together in a safe place lest you accidently step on them! The answer is then a needlecase.

A needlecase-style for 'Viking' ladies, that has been gaining popularity in recent years [editorial note: circa 2010 in south-eastern Australia], is a vertically-hanging hollow bone, with a strip of leather running through, into which the needles are inserted. A stopper on the end of the thong keeps the protective bone case from falling off. I admit, I am yet to be convinced that they were used during the Viking age, but there is modern ethnographic evidence of the Saami and Inuit using a similar arrangement.

Examples of this style of needlecase, from the McCord Museum:

Click on images to enlarge

Left: Needlecase. Western Arctic Inuit: Inuvialuit. Circa 1857.

Ivory, glass beads, sealskin, sinew

24.5 x 6 cm

Centre and right: Needlecases. Arctic Saami. Circa 1850-1910.

Bone, cord

9 x 1.3 cm

Photographs from SaamiBlog and the McCord Museum, under a Creative Commons License.

When looking at the needlecases at the SHM website, in contrast to the Arctic examples, the extant hollow bone finds appear to have been suspended horizontally. The clue is in the holes that piece one side of the bone tube, half-way down its' length. This matches up with sheet-metal counterparts that have also been found, either with identical piercings, or with a loop attached at the same point. It is likely that this loop would then attach to a chain or string, and attached to ones' clothing. (Hägg, 1996) The needles were inserted into a scrap of cloth, which was then stuffed inside the case to keep it in place. (MacGregor, 1985; 193) An alternate technique is to place the needles inside, and then stuff one or more of the ends with unspun wool (Goslee, 2009 quoting MacGregor 1997) or a bung (Beaudry, 2006; 71).

It is my personal opinion, that this horizontally-worn needlecase design is more likely to have been worn by a Viking-age Norse woman.

Horizontal Needlecases

Bone needlecases, showing chain attachment:

Photos by Yliali Asp (left) of SHM 9259, and Sara Kusmin (centre and right) of SHM 21802.

Bone needlecases, with perforations in the middle of the case:

Photos by Yliali Asp (left and centre) and Sara Kusmin (right) of SHM 5208.

Metal needlecases

Photos by the SHM of 2976, Yliali Asp of SHM 28364, and Eva Vedin of SHM 10501.

Needlecase photos used under a Creative Commons license.

Thimbles

According to Beaudry (2006; 89), the earliest thimbles found in Europe date from the 9th century, and it is highly likely that it was a ring-style of thimble, instead of the typical domed type used today (ibid.; 93).

Tools for Thread Production

Spindle Whorls

Photos by Yliali Asp of ceramic (left) and amber (centre) whorls, and Sara Kusmin of stone whorls (right) SHM 5208

Spindle Sticks

Bronze spindle whorl with fragment of wooden spindle, by Elisabet Pettersson.

Used under a Creative Commons license.

Of course, after one has made the thread, one needs to stabilize or 'fix' the threads through various processes, and then store it. The Oseberg burial contained a wealth of tools for this, including a niddy-noddy and swift (Pulsiano and Wolf, 1993; 99), as well as completed balls of thread (Brøgger, 1921; 6). Østergård suggests one way of making these balls is with a shaped stick called a nostepinne or nøstepinde (2004; 52).

Photo of the Oseberg niddy-noddy by Cassandra. Used under a Creative Commons license.

For photographs of the swift (yarn-winder) from the Oseberg burial, search for 'garnvinne' at the Universitetsmuseenes Fotoportal site.

Measuring

By the time the Icelandic law code, the Grágás, was written down in the 12th century, the standard cloth measurement was the ell. It was equivalent to 490 mm (Østergård, 2004; 63), or about 19 2/8" (Ward, 2010). However this does not answer how measurements were obtained, and then transferred to the fabric.

Maintenance: Whetstones

Needles and blades had to be kept sharp, and the solution was to use a whetstone (Østergård, 2004; 112). Made of sandstone, these whetstones were from local or imported Norwegian quarries, and are often strikingly beautiful because of their striped surface. They could be pierced, and threaded with a metal ring or cord so they doubled as jewellery. Although reproduction whetstones are expensive, their modern equivalents can be purchased cheaply at fishing and tackle shops -- for sharpening fish hooks -- although they are not nearly as attractive.

Pierced whetstones

Photos by Yliali Asp (left) of SHM 7250, Sara Kusmin (centre) of SHM 5404, and SHM of 34000 (right).

Used under a Creative Commons license.

Maintenance: Wax

A lump of wax, found in a bucket of sewing and weaving tools from the 9th century Oseberg burial (Brøgger, 1921; 6), may indicate that lightly waxing a thread may have helped with sewing. Today, handsewers may run their sewing thread across a block of beeswax in order to smooth the thread, making sewing easier. As beeswax was considered an expensive commodity at the time (Avdusin and Puškina 1988; 30), however, it is impossible to say what use the Oseberg wax lump was originally intended for.

Bibliography

Websites last checked 22 September 2022.

- Anonymous (2009) York Archaeological Trust Online Picture Library

- Anonymous (2009) McCord Museum: Needlecases

[Link no longer works, use the McCord Stuart Museum Collections Search] - Anonymous (2009) SaamiBlog: Saami pewter embroidery, belts, purses and bone ornament decor - Samiske tinnbroderi, belter, vesker og beindekorasjoner

- Anonymous (2009) SCABasketry: Files: Viking Age Baskets

[Yahoo Groups no longer exist and the page was behind a login, instead use this archived page from Baldurstrand Re-enactment for similar photos.] - Arwidsson, Greta and Berg, Gösta (1983) The Mästermyr Find, A Viking Age Tool Chest from Gotland (Stockholm: Kungl. Vitterhets Historie och Antikvitets Akademien)

- Avdusin, D.A. and Puškina, T.A. (1988) "Three Chamber Graves at Gniozdovo" Fornvännen 83; 20-33.

- Beaudry, M.C. (2006) Findings: the material culture of needlework and sewing (New Haven: Yale University Press)

- Brøgger, A.W. (1921) The Oseberg Ship

- Engevik jr., A. (2002) "Spannformede leirkar - forbilder og funksjon" Viking 65; 49-69

- Goslee, Sarah (2009) Silver Needlecase

- de Holacombe, Christian and de Neuville, Michaela (2005) "A Period Workbox" Filum Aureum 28

- Hall, Richard, (1984) The Viking Dig, (London:The Bodley Head)

- Hägg, Inga (1996) “Vikingatidens Kvinnodräkt” Historiska Nyheter; 12-14.

- Lewins, Shelagh (2003) The Partly-Completed Tablet Weaving from the Oseberg Ship Burial

- MacGregor, Arthur (1985) Bone, antler, ivory and horn: The technology of skeletal materials since the Roman period. (London: Ashmolean Museum)

GoogleBooks Preview - Østergård, Else (2004) Woven into the Earth: Textiles from Norse Greenland (Aarhus: Aarhus University Press)

- Pulsiano, P. and Wolf, K. [Eds.] (1993) Medieval Scandinavia: an Encyclopedia (New York: Garland); 96-100.

- Roesdahl, Else, and David M. Wilson (1992) From Viking to Crusader: The Scandinavians and Europe 800-1200. (New York: Rizzoli.)

- Schuster, Robb The Gokstad Backpack

- Universitetsmuseenes Fotoportal

- Ward, Christie Units of Measurement from Viking Age Law and Literature

- Watson, J. 2009-10. "Hollow swords and needles in a soil block: Unravelling the evidence preserved on the artefacts from the Viking cemetary at Cumwhitton, Cumbria" English Heritage Research News 13; 14-16.