Medieval Baltic

Medieval Europe

The Court of King Arthur: Merchant Guild or Proto-Medievalists?

An abridged version of this essay appeared in issue 35 of the SCA magazine Cockatrice.

The original article appeared in issue 55 of Slovo: The Newsletter of the Slavic Interest Group. Revised and Updated.

It is likely, if you are reading this, that you are a person interested in history. You may even be the sort of person who may take part on the occasional weekend, or longer, at 'living-history' events like Medieval Week in Sweden on Gotland, or the broad-focused Pennsic War in Pennsylvania, U.S.A.

People have been taking part in activities designed to capture the essence of a particular time period for a very long time. One such example is from the middle ages itself, aiming to recreate the legendary Court of King Arthur.

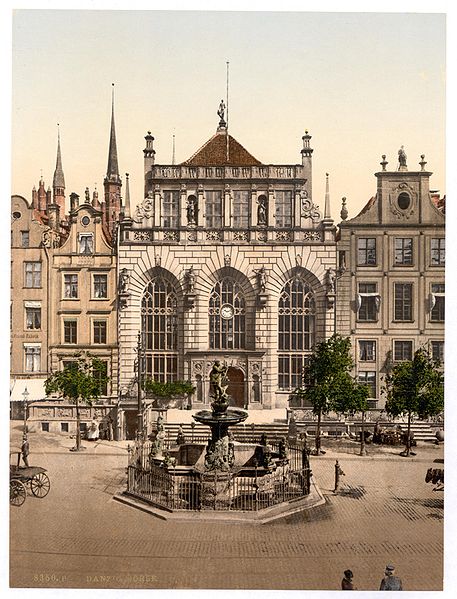

Even in the 14th century, the desire to re-live a 'golden age' of high culture and the chivalric ideal, was an attractive idea. The merchant class in Danzig (Gdańsk), Poland, were no exception to this siren song, and the mercantile Brotherhood of St. George built their very own Court (Wallace, 2007). Centred on Poland, and spreading throughout the Hanseatic trade routes of the Baltics, similar courts appeared in Riga, Elbląg, Rewal (Tallinn), Brunsberg (Braniewo), Thorn (Toruń), Culm (Chełmno), and Stralsund (Schlauch, 1959). These buildings were named in honour of the mythical king and his round table as the Court of King Arthur, (German: Artushof, Latin: Curia Regis Artus, Polish: Dwór Artusa), and the Gdańsk building still stands to this day.

A Late 19th/early 20th colour lithograph of the building in Gdańsk.

Source: Wikimedia.

It is fallacious, however, to draw parallels between modern re-creation groups, striving to reproduce an idealized time, and those first faltering steps of the Artushöfe. Arthur was seen as the epitome of knightly virtues and chivalry; his round table was a symbol of equality and partnership amongst the brotherhood. A rose-tinted view of an idealized period draws parallels with the modern-day complaint from some historians that modern recreations use small groups of individuals dressed and acting in a manner too similar and high-class to accurately portray society (eg. Dawson, 1999 and 2001). While the Court is rememberted today as a place of feasting, jousting tornaments, dancing and frivolity (Gdańsk History Museum, 2009), at the time it was likely to have been perceived as an aristocratic club, combining feudal ceremonies, a religious benevolent society and banking. Although the courts were a major source of 'social contacts between and amongst locals and foreigners' (Graf and Gelderblom, 2009) they also acted as a way of keeping the German-speaking merchant class culturally homogenous, as they were a major social outlet where one had to abide by societal norms (Schlauch, 1959).

A modern photo of inside the Court in Gdańsk. The interior dates to the 18th century (Gdańsk History Museum, 2009).

Click on image to enlarge.

Source: Wikimedia.

Like the knightly order the merchants were trying to emulate, members of the Brotherhood were held to high standards of ideal behavior. According to an early 'Artushofordnung' allegedly from 1300, “quarreling, bad language, commercial malpractices, intimacy with eachothers' wives and marriage of women with bad reputation” would result in disqualification from the Brotherhood (Schlauch 1959, trans. Simson 1900).

Members of the Artushof were drawn from the merchants and burghers of Polish society (Kmetz, 1994), which may resonate with the decidedly middle-class background of many people involved in re-enactment today (Coles and Armstrong, 2008). However it seems that guests and members of the Brotherhood were also required to be of noble standing (Gdańsk History Museum, 2009), and male. Skilled laborers, hired workers as well as female merchants and craftspeople were excluded from the Brotherhood into the 16th century (Schlauch, 1959).

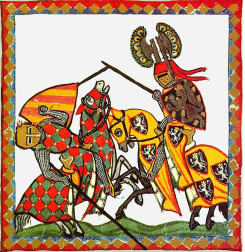

Annual ceremonies included 'tournaments held in knightly costumes,' although if this included historic dress as well as amour seems to be unclear (Schlauch, 1959). Although it is tempting to picture a high-medieval Polish man attempting to dress as a 6th century Saxon from the supposed time of King Arthur, it is highly unlikely that the chivalric activities of the Brotherhood of St. George would be considered to have been a re-enactment of any time period – real or imagined – by any modern observer. It would be impossible to know for certain what a participant in such spectacles thought, too.

Jousting from the 14th century German Manesse Codex.

Source: Wikimedia.

As seductive as it may be to see these members as proto-medievalists, in reality the situation was probably much more ordinary. If anything the court, in day to day activities, was more akin to a gentlemen's club, known throughout the Baltic trade routes. It is known that food and drink was served at the court daily, excepting Sundays and special occasions, until 10pm (Simson, 1900; Schlauch, 1959). Foreigners visiting from other Hanseatic towns was a frequent occurrence (Schlach, 1959), but for locals it formed part of the daily routine. “For it is the maner in Danswycke [Danzig] that the moste parte of all the merchaunte men have supped at vii. a clocke, and than they goe to Artus gardeyn to drinke and there to take there recreacyon, and sometyme to make bargains with theyr marchandise.” So explains a wife who knows when her lover would be able to visit safely, in the 1560s fictional text The Deceyte of Women (Schlauch, 1959).

It was a place for the merchants to trade and strike deals, disseminate and receive information, and hear announcements from the authorities (Gdańsk History Museum, 2009). The acquisition of money, albeit wrapped in a knightly chivalric guise, is more likely to be the principal aim of the members of the Brotherhood than a modern-day interest in the past.

Sadly, by the late 16th and early 17th centuries, war, disease and turmoil struck Poland, and the Court was not immune. The feasts and frivolity that had marked its existence through the middle ages declined, until the 18th century when it became the Danzig stock exchange (Gdańsk History Museum, 2009).

Yet the Artushof remains to this day an interesting quirk of history, and shows that re-creating and re-enacting elements from an idealised past has been happening for longer than one might think.

Bibliography

All links checked 22 September 2022.

- Coles, J. and Armstrong, P. 2008. "Living History: Learning Through Re-enactment" 38th Annual SCUTREA Conference, University of Edinborough.

Available online, at: https://www.levantia.com.au/questions.html - Dawson, Timothy. 1999. Beyond Re-enactment: Rescuing History from Recreation

Online at: https://www.levantia.com.au/rescue.html - Gdańsk History Museum. 2009. Artus Court

Online at: http://www.mhmg.gda.pl/oddzial/11/artus-court - Graf, Regina and Gelderblom, Oscar. April 13. 2009. The Rise, Persistence and Decline of Merchant Guilds: Re-thinking the Comparative Study of Commercial Institutions in Pre-modern Europe Economic History Workshop Yale University.

Available online, via the Past Seminars webpage at: https://economics.yale.edu/sites/default/files/files/Workshops-Seminars/Economic-History/grafe-090413.pdf [PDF] - Kmetz, J. 1994. Music in the German Renaissance. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.)

- Schlauch, M. 1959. King Arthur in the Baltic Towns. Bulletin Bibliographique de la Société Internationale Arthurienne 11: 75-80

- Simson, Paul. 1900. Der Artushof in Danzig und seine Brüderschaften, die Banken. Danzig: T. Bertling.

Available online at http://www.archive.org/details/derartushofindan00simsuoft. - Wallace, D. 2007. “Margery in Gdansk” William Matthews Memorial Lectures, Birkbeck University of London.

Available online at: http://www.bbk.ac.uk/events/matthews/david_wallace